News & Commentary

When Black Mourners are Threatened with Official Violence

Carl Takei, Former Senior Staff Attorney, ACLU’s Trone Center for Justice and Equality

In early June

By Carl Takei, ACLU National Prison Project

Our New Interactive Tool Helps Texans See the Impact of Jails on Taxpayer Dollars – and Human Lives

The size of someone's bank account shouldn't determine whether they live or die in jail during the ongoing pandemic.But today, tens of thousands of Texans – disproportionately people of color and low income people – sit in jail as they await trial because of money bail. People with enough resources can buy their freedom and await trial in their homes and communities, while people without enough resources remain stuck in jail. In addition to facing the possibility of losing their housing and their jobs, people locked up because of unaffordable bail now face an increased risk of dying from COVID-19.Not only is money bail unfair and dangerous, it’s also expensive: Jailing people who have not been convicted of crimes costs Texas taxpayers an estimated $905 million each year.We need meaningful bail reform now more than ever to protect all people who interact with the criminal legal system and to reduce the enormous burden that pretrial incarceration puts on our communities.That’s why today, the ACLU of Texas is launching a free, new, interactive online tool developed in collaboration with Houston-based data science and technology firm, January Advisors. The Texas Jails Data Dashboard tracks COVID-19 cases in Texas jails, visualizes the enormous financial costs associated with pretrial incarceration, and allows people to see how Texas county jail populations have changed, both during the COVID-19 health crisis and before.The free online tool culls information from the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, allowing policymakers and journalists to see how incarceration rates and COVID-19 cases in jails have changed since January. It allows visualizations of jail population data going back to 1998, provides comparisons in pretrial incarceration rates between counties using the latest available data, and helps policymakers, journalists, and the public understand the cost to local taxpayers of high rates of pretrial incarceration.The tool is a straightforward rendering of a complicated layer of our criminal justice system, the motivation for which is guiding policy change. Data from the dashboard shows that jail populations in many Texas counties dropped in April in response to the COVID-19 epidemic, but that in many cases, jail populations are on the rise again. Sadly, there are thousands of reported COVID-19 infections among guards and incarcerated people, the data shows. Finally, the dashboard shows that a majority of individuals detained in Texas jails are held pre-trial, and in most cases, these people are presumed innocent but are only kept in jail because of their inability to afford cash bail.Using the dashboard’s “Policy Simulator” feature, users can see the impact of mass incarceration in Texas jails on taxpayers. For example, a 25 percent reduction in jail populations statewide would save Texas taxpayers more than $198 million annually.Fixing our unjust money bail system in Texas begins with helping everyone understand the scale of the problem. With this new tool, we aim to make publicly-available data about Texas Jails accessible and actionable - moving advocates, organizers, journalists, and policy makers towards smart justice.Explore the Dashboard for yourself to find out how our existing system is costing taxpayers millions and endangering lives, then take action to fix Texas’s broken bail system.

By Nick Hudson

Prosecutors Disappoint During the Pandemic — 3rd Edition

As the COVID-19 pandemic threatens to become a death sentence for people trapped in prisons and jails across the U.S., the actions — or inaction — of prosecutors to decarcerate have had a tangible life or death impact. We examined the responses from prosecutors in the 15 biggest cities in this country. This is the third and final post in the series — you can also read the first and second.11. Austin, Texas Austin’s Margaret Moore understood the need to respond to the pandemic’s threat to people living and working in local jails. She played a significant role in bringing judges to the table to proactively work to save lives during COVID-19. The judges decided to grant no-cost bonds whenever practical to clear jail space, resulting in a dip in the jail population. As of May 12, Travis County’s adult jail system held about 1,600 people and had no positive test results. But test accessibility is distressingly low — only about 1 percent of the county’s average jail population was tested during the pandemic.Unfortunately, Moore otherwise had an unclear role in Travis County’s pandemic decarceration efforts — unlike prosecutors across the country declining to prosecute various offenses, identifying people to be released from jail, and fighting back against short-sighted restrictions by the Texas governor’s executive order limiting pretrial releases. By mid-March, her re-election opponent, Jose Garza, publicly called upon her and other city officials to do more to decarcerate jails and prisons, thereby removing hotbeds for the spread of the disease. In mid-July, voters weighed in on her limited action, choosing Garza as the Democratic candidate for November’s prosecutor election. 12. Jacksonville, Florida Jacksonville’s Melissa Nelson took early, swift action to save lives facing the pandemic in local jails. By late March, she made a temporary plan to release a significant number of people, directing her office to offer plea deals that avoid jail time, release some people pre-trial, not filing charges in non-violent “marginal” cases, and determining whether a time-served and/or probationary sentence is appropriate in any nonviolent case where the state is currently offering one year of jail time or less. The result of these policies: By late April, the number of people held in the Duval County jails fell by 21 percent. These are positive outcomes, but Nelson’s policies still fall short of helping everyone potentially vulnerable to the virus by unilaterally choosing not to consider those accused or convicted of violent or sexual offenses, rather than reviewing their circumstances before making a decision.13. Fort Worth, Texas Fort Worth’s Sharen Wilson has been extraordinarily silent as the pandemic sweeps across the country, despite the deathly threat it poses to those trapped in jails and prisons. But Tarrant County judges and sheriffs picked up her slack, holding court proceedings to grant bonds or shorten sentence lengths so people could get released sooner. Unfortunately, Wilson seems to have continued business as usual — including seeking enhancements against people for low-level offenses, such as trespassing, failing to acknowledge that forcing people to spend more time behind bars during a pandemic could have fatal consequences. 14. Columbus, Ohio In Columbus, Ohio, two prosecutors share responsibility for the city’s criminal system — Franklin County Prosecutor Ron O’Brien handles felony cases, while Columbus City Prosecutor Zach Klein has jurisdiction over misdemeanors. Both made small steps towards helping people behind bars as the coronavirus spread throughout the country, but fell short of making the deep changes necessary to save lives.In late March, Klein announced that his office was already working on criminal justice reform that would “jail only those that need to be locked up,” without providing any details on who that would include. He also expressed concern about crafting blanket policies for release. Instead, jail drops between the start of the pandemic and March 24 largely flowed from sheriffs using alternatives to arrest more often to avoid bringing people to jail.O’Brien has taken a few steps in the right direction, including limited court proceedings and only pursuing new, serious felonies. However, he did not proactively review cases involving people serving their sentences. Moreover, O’Brien expressed concern about not being more involved in court decisions to release eight youths from a juvenile detention center where the outbreak struck nearly half of the incarcerated youth and about a quarter of the staff. These small gestures toward release simply do not go far enough.15. Charlotte, North Carolina Charlotte’s Spencer Merriweather quickly worked to change his pretrial policies in response to COVID-19. At the beginning of the pandemic, his office released a statement saying they have and will continue to work diligently to ensure that the only people in pretrial custody during this crisis are the people he believes pose a risk to public safety. Merriweather claims the initiatives launched by his office to limit pretrial custody of people accused of nonviolent offenses have reduced incarceration by 14 percent since the start of the pandemic. Although he has shown flexibility on pretrial policies, Merriweather has not focused at all on those already serving sentences, even as nearby prosecutors do. Decarcerate Mecklenburg, a coalition of community activists, attorneys, and religious leaders, held rolling protests in vehicles circling Mecklenburg County Detention Center, the District Attorney’s Office, and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police headquarters, demanding in part that Merriweather release people held on bond along with those with six months or less on their sentence, pregnant women, and everyone over 50 years of age. Without action for those vulnerable but already serving time, Merriweather is leaving hundreds if not thousands of people behind bars to face a deadly virus. In fact, in late July, more than 40 people at the Mecklenburg County Detention Center have tested positive for Coronavirus.The Takeaway When advocates began in early March to ring the alarm that people living and working in jails and prisons were particularly vulnerable to contracting the coronavirus, criminal system stakeholders sluggishly responded. Then it hit — prompting police, sheriffs, public defenders, judges, corrections officials, and government actors alike to work together to begin slowing the number of people coming into the system and releasing people who were especially vulnerable.Many prosecutors stepped up — this analysis, though specifically focused on the largest 15 cities in the United States, shows that. But, as the most powerful figure in the criminal legal system, prosecutors can and must do more. As COVID-19 continues to spread through jails and prisons, prosecutors must expand their initial efforts — expand the kinds of cases they outright dismiss, recommend more releases before trial, divert people into programs that will help them avoid being trapped in these facilities, recommend alternatives to incarceration after conviction whenever possible, and proactively support the release of particularly vulnerable people from both jails and prisons.The reality is that prosecutors were — and still are — in an ideal position to prevent COVID-19 from turning into a death sentence for people behind bars. Now, it’s time for them to act.

By Nicole Zayas Fortier, Weronika Burza

Prosecutors Disappoint During Pandemic — 2nd Edition

Nicole Zayas Fortier, Policy Counsel, ACLU Campaign for Smart Justice

By Nicole Zayas Fortier, Weronika Burza

Prosecutors Disappoint During the Pandemic

Nicole Zayas Fortier, Policy Counsel, ACLU Campaign for Smart Justice

By Nicole Zayas Fortier, Weronika Burza

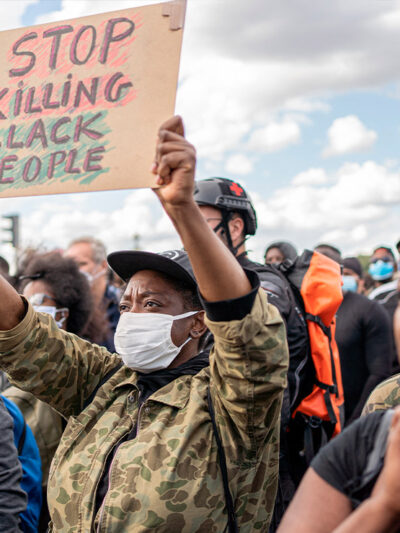

Dallas Police Killed My Unarmed Son. Their Brutality is a Global Problem.

Collette Flanagan, Founder, Mothers Against Police Brutality

In 2

By Collette Flanagan, Founder of Mothers Against Police Brutality

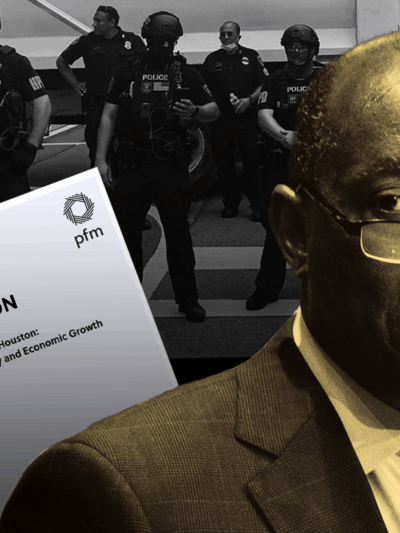

Mayor Turner, We Need Action on Police Reform, Not More Study

This piece was originally published in the Houston Chronicle.

By Tarsha Jackson, Terri Burke

Progress Report: Houston Police Reform

In 2016 and 2017, Mayor Sylvester Turner commissioned two major reports that address police reform. The Mayor’s Transition Committee on Criminal Justice was composed of 26 community leaders, elected officials, academics, and criminal justice reform advocates. It made eight recommendations for reform in March 2016.

By Nick Hudson

El Paso City Council: Keep the Police Department Accountable

On June 8, ACLU of Texas policy and advocacy strategist, Adri Perez, testified before the El Paso City Council to call on its members and the mayor to take meaningful action in holding the El Paso Police Department accountable. Below is a transcript of the testimony Adri gave before the council.

By Adri Perez

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.