In a U-shaped room, 30 defendants, mostly men ranging in age from their early 20s to late 40s, hurriedly walk into the court, all chained together around their waists and wrists. Some look tired, others look defeated.

None are being charged with a violent crime, although that’s hard to imagine thanks to the boisterous sounds of metal chains clinking together.

They are present at the federal court in Brownsville before a magistrate judge being criminally charged with entering or re-entering the country. In legalese, they have violated Title 8, Sections 1325 and 1326 of the U.S. Code. These offenses carry misdemeanor and felony charges, respectively, with the potential for decades of jail time and hefty fines.

If these federal laws sound vaguely familiar, it's because they got a public boost of attention when then-presidential candidate Julian Castro called for their end. Castro argued that these federal laws, based on racist ideologies popular in the 1920s, were wasteful, unnecessary, and worsened mass incarceration problems.

In fact, these policies have been a massive resource drain on our court systems. Since 2005, when the criminal prosecutions of “unauthorized border crossers” skyrocketed under George W. Bush’s administration, the cases have accounted for 57 percent of federal filings.

Worse, the laws exacerbated the tragedy of family separation under the Trump administration’s disastrous zero-tolerance policy. In the late spring of 2018, the federal government began ripping away thousands of children from their parents who were being prosecuted for mere misdemeanors under these laws. Despite promises to do so, hundreds of children have yet to be reunited with their parents. The costs have been tragic and traumatic.

The federal courthouse in Brownsville, Texas.

The ACLU of Texas is at the federal courthouse in Brownsville almost every week watching similar scenes. During the time we observed these 30 defendants, we were with a small group of pastors visiting from a Dallas-area Baptist church who looked on from the audience of the courtroom.

They came as volunteers for the “Ports and Courts” program the ACLU of Texas began in August 2018. The program is an effort to bring faith-based groups from around the state to see and experience what is happening with the immigration crisis at our southern border, including the mass criminal prosecution of migrants. The times we live in demand that we join together various groups to collectively confront the wasteful injustices that are occurring in our communities.

The times also demand that we ask ourselves vital questions on how to move forward with more human-centered solutions: What if we decided to stop criminally prosecuting migrants who seek refuge or economic opportunity at our border? What if we instead focus our energies and resources on achieving a humane immigration system and reducing our reliance on the mass incarceration of people seeking safety?

A group of pastors from a Baptist church in Dallas visit the federal courthouse in Brownsville to observe the Title 8, Section 1325/1326 prosecutions.

Back in the courtroom, an employee went around taking attendance from each defendant. They all had interpreter headsets, some falling out of their ears, in order to understand her. Prosecutors and administrative staff chatted and smiled in the middle of the room at a large wooden table. The judge emerged and the hearing began.

“Si” the 30 defendants shout loudly in unison to the Spanish interpreter after she reads their rights en masse and asked if they have understood.

It’s hard to believe all have totally grasped the seriousness of the charges and the potential consequences. After all, the 30 individuals before the federal judge shared just one public criminal defense attorney with whom they have spent a few minutes that same morning. Meanwhile, there were five prosecutors representing the government. All defendants pled guilty in agreement for a reduced sentence.

The one defense attorney did his best to explain tidbits of each individual’s plight. Almost all were looking for work to support their children.

“He has a family of five, your Honor.” “He has a sick child, your Honor.” “He is an agricultural worker who has been out of work for six months, your Honor.” These explanations were euphemisms for describing people suffering from the crushing effects of poverty.

The timid apologies from the defendants to the judge came one by one, as he chastised each person individually for breaking the law, warning them that there would be stiffer consequences next time.

Federal marshals then led the defendants out of the courtroom and back into the custody of the Border Patrol. The door closed, leaving behind the image of frightened people who had, many for the first time in their lives, been found guilty of a crime.

One of the Dallas pastors noted, later that day over coffee, that he did not recognize those proceedings as “American in any way shape or form.”

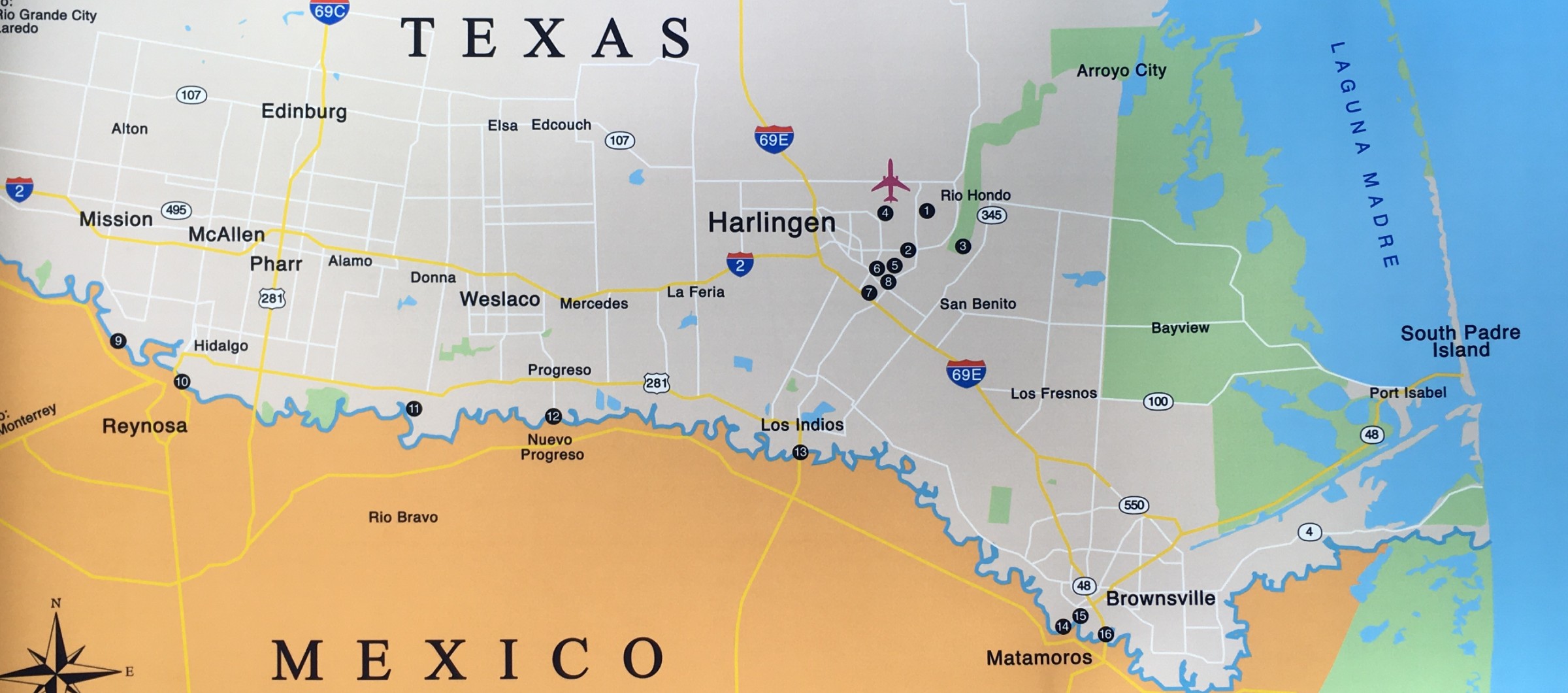

A map of the Rio Grande Valley demonstrating part of the broad stretch of border Texas shares with Mexico.

Many Texans residing in the borderlands regions like the Rio Grande Valley will tell you that the impact of federal law locally has been disastrous. They have lived, worked, played across the invisible line which separates us from Mexico for generations, and have experienced first hand the ebb and flow of policies that have negatively impacted their livelihood.

In the end, the conversations we need to be having collectively are about our federal government making unjust decisions that affect vulnerable families and individuals seeking a better life, while simultaneously putting a huge strain on the federal criminal justice system.

It is a difficult time for someone who seeks safe harbor in the United States. It is an urgent time for those whose values — be they biblically or constitutionally-based — call them to action. One step is to bear witness: come to the border, go to court, visit asylum seekers. A second step is to lift up the testimony of those who have gone to the trouble of doing the hard work of witnessing, like many of the visitors from the Ports and Courts program have done.

Take those voices and that witness to the statehouse; take it to your polling place. Bring a friend. Bring your neighbors. Bring your community.

Voices of the Rio Grande Valley: How Extremist Federal Policies Continue to Threaten Texas’ Borderlands. The ACLU of Texas, in collaboration with staff and community members based in the Rio Grande Valley (RGV), will be sharing a series of essays, photos, and videos that demonstrate the region’s ongoing struggle to ward off intrusion of federal policies on everyday life. While many of these policies are not new to the RGV, they have been ramped up under the Trump administration, which has used the borderlands, its people, and its resources as pawns in a political game. But the people of the Rio Grande Valley are not staying silent. Join us as we explore the rich history, culture, and environment of this region in southeast Texas, and how its residents are fighting back to preserve their homes and way of life.